Critics like to say that the horror genre was basically dead in the ‘90s, with most long-running horror franchises like

Halloween,

Friday the 13th, and

A Nightmare on Elm Street going dormant, replaced by quiet direct-to-video stuff or the bigger glories going to prestige thrillers like

The Sixth Sense,

Seven, and

The Silence of the Lambs. Being that I’m one of those folks who believes the horror genre

never goes away and

can’t die, I still have to admit that the genre seemed to be on life support during that ten-year stretch, with very few notable exceptions like

Candyman and…

Pet Sematary Two (lol). After

Scream came along in 1996 and kick-started the slasher sub-genre, that was nearly the only kind of horror flick to get the greenlight. When news came down during the late ‘90s that Hollywood super producers Joel Silver, Robert Zemeckis, and Gilbert Adler were going to be forming Dark Castle Productions, with its aim to create big-budget remakes of director William Castle’s filmography, it felt like an event. It felt like they’d somehow already earned the reputation that Blumhouse began to enjoy after years of home runs – but without having made a single movie.

The first of these productions was 1999’s House on Haunted Hill, directed by William Malone and starring the likes of Ali Larter, Taye Diggs, Chris Kattan, and with Geoffrey Rush stepping into the shoes previously occupied by the legendary Vincent Prince. Except for a disappointing finale hampered by too much (terrible) CGI, House on Haunted Hill was an excellent update on a famous property, resurrecting Castle’s penchant for over-the-top spookshow-isms but now adorned with Malone’s own penchant for eerie, Jacob’s Ladder-like imagery. In the right frame of mind, it was both visually scary and even kind of a mind-fuck. Horror fans weren’t the only ones pleased, as the flick did great business at the box office, boding well for the brand new Dark Castle’s future. Not wanting to tempt fate too much, they moved forward with their next William Castle update: 1960’s 13 Ghosts – one that, in keeping with Castle’s proclivities for gimmicks, required audience members to wear special glasses (read: 3D glasses) so they could “see” if the movie’s ghosts were trying to come off the screen. And with the announced cast of Tony Shaloub, Matthew Lillard, and none other than F. Murray Abraham, it seemed a safe assumption that the newly dubbed Thir13en Ghosts would be every bit as successful as House on Haunted Hill.

It wasn’t.

Instead, Thir13en Ghosts proved to be the walking, screaming, over-edited, and over-produced definition of the sophomore slump, trying to take everything that made House on Haunted Hill work as well as it did and dialing it up to eleven while allowing everything else to fall by the wayside. Instead of there being one cumulative ghostly threat with a name and face (Jeffrey Combs's Dr. Vannacutt), now there’s thirteen; instead of there being a fascinating gothic house with a lot of character, thanks to its twisting hallways where people can get lost and disappear, now there’s a house that’s forced to actually embody a character and made entirely of see-through glass…where people can still get lost and disappear, anyway; instead of the amped up guy from SNL playing the neurotic comedy relief, there’s the even more amped up guy from Scream playing the neurotic comedy relief. Thir13en Ghosts was trying way too hard to replicate what House on Haunted Hill seemed to do so easily – preserve the plot of the original movie but with a twist, design some creepy spooks, and offer us a handful of characters who earn our sympathies without the need for an exploitative painful history. (Mom dead, details later.)

The characters in Thir13en Ghosts are paper thin, from the mourning widower/father Arthur Kriticos (Shaloub) to his two kids, Kathy (Shannon Elizabeth, who is incapable of playing a real person), and Bobby (Alec Roberts), the youngest, most precocious member of the family, and you can tell he’s precocious because when things go wrong, he’s weawwy sowwy. And please, let us not forget Maggie (an early 2000s relic known as Rah Digga), the family’s housekeeper and nanny, who, in the course of 90 minutes, never washes a single dish or folds a single piece of laundry, who literally sits at the kitchen table with rollers in her hair filing her nails as Arthur trips over a wayward toy left in the middle of the floor and who makes no attempt to pick it up, who doesn’t do a single maternal/domestic thing for either child, and who even loses Bobby within minutes of the family entering the infamous house and after being told by Arthur not to let him out of her sight. “Aunt Maggie doesn’t do windows!” she jokes after seeing the family’s new, inherited all-glass house, but it’s not much of a joke because Aunt Maggie doesn’t seem to do anything. Though the family is bland, Matthew Lillard does his damndest to inject some life into the movie, trying on the new archetypal funny/manic character that Chris Kattan had seemingly created in House on Haunted Hill. He is nearly Thir13en Ghosts’ sole heartbeat, along with Embeth Davidtz (Army of Darkness) trying the most as Kalina the ghost activist (don’t think about this too hard) and the esteemed F. Murray Abraham, who still manages to radiate menace and chilliness even though you can tell he’s definitely not into this.

The showpiece of Thir13en Ghosts was meant to be the glass house where the majority of the movie takes place, built with winding hallways and filled with pre-war curio and mystical occult paraphernalia. On paper, this sounds interesting. The problem is the movie fails at establishing the geography of this very house from the very beginning – how big is it? how many rooms are there? where the hell is it, anyway? – and with every hallway and bedroom and study being framed with glass etched in scrolling Latin script, everything looks the exact same. Unless you see a golden telescope or an old-fashioned porcelain bathtub, it’s almost impossible to know where anyone is, or where they are in relation to everything else.

Director Steve Beck makes his directorial debut after having established a respectable career as a special effects artist in notable titles like The Abyss, and though he exercises some flair behind the camera, as evidenced by the opening shot panning across a single room that goes from happiness and joy to death and despair, once the novelty of seeing ghosts appear and disappear a few times in the same few frames, you realize that’s the only trick he’s got. Soon after, the flick’s so-called entertainment value comes from watching shallow characters wander hallways and run from ghosts, the designs of which look cornier and cornier the longer they’re on screen (except for ‘The Princess’– she’s legit creepy from her first Shining-inspired appearance until her last).

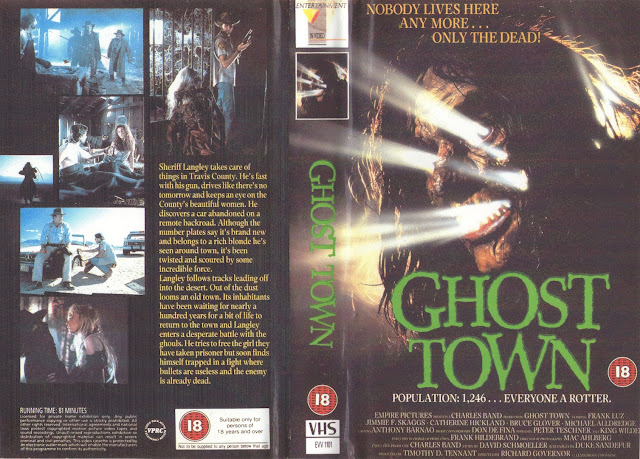

Still, like its predecessor, Thir13en Ghosts opened well to big business, but unlike its predecessor, audiences weren’t too thrilled with the results. For some reason, following the poor reception from audiences and critics, Dark Castle tweaked their original mission statement and never did another William Castle remake again, filling their slate with original content (Ghost Ship, Gothika), a remake of a non-Castle property (House of Wax), and, eventually, non-genre stuff (Guy Ritchie’s Rocknrolla, Ninja Assassin). I should mention, though, that they also produced 2008’s Orphan, a movie so viciously stupid and stupidly vicious that you have to see it to believe it.

I’ll be honest when I say that, even though Dark Castle produced far more losers than winners, I miss them as a brand. Though, as mentioned, Blumhouse has taken over and delivered far more consistency to theaters, either with their resurrections of older properties or with original ideas, I miss the era when studios were actually okay with throwing multi-million-dollar budgets together for R-rated horror productions. It was a short-lived era, and one we’ll never see again thanks to the roaring success of micro-budget horror, but the genre has always existed in a cyclical fashion, so maybe they’ll come back one day and remake The Tingler with Jon Hamm or something. Until that day, there’s always revisiting House on Haunted Hill, because these Thir13en Ghosts are about thirteen too many.